Labor Union

An association, combination, or organization of employees who band together to secure favorable wages, improved working conditions, and better work hours, and to resolve grievances against employers.

The history of labor unions in the United States has much to do with changes in technology and the development of capitalism. Although labor unions can be compared to European merchant and craft guilds of the Middle Ages, they arose with the factory system and the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century.

The first efforts to organize employees were met with fierce resistance by employers. The U.S. legal system played a part in this resistance. In Commonwealth v. Pullis (Phila. Mayor's Ct. 1806), generally known as the Philadelphia Cordwainers' case, bootmakers and shoemakers of Philadelphia were indicted as a combination for conspiring to raise their wages. The prosecution argued that the common-law doctrine of criminal conspiracy applied. The jury agreed that the union was illegal, and the defendants were fined. From that case came the labor conspiracy doctrine, which held that collective (as distinguished from individual) bargaining would interfere with the natural operation of the marketplace, raise wages to artificially high levels, and destroy competition. This early resistance to unions led to an adversarial relationship between unions and employers.

Between 1806 and 1842, the labor conspiracy doctrine was applied in a handful of cases. Then, during the 1840s, U.S. courts began to question the doctrine. The most important case in this regard was Commonwealth v. Hunt, 45 Mass. (4 Met.) 11, 38 A.M. Dec. 346 (Mass. 1842), in which Chief Justice LEMUEL SHAW set aside an indictment of members of the bootmakers' union for conspiracy. Shaw agreed with employers that competition was vital to the economy but concluded that unions were one way of stimulating competition. As long as the methods they used were legal, unions were free to seek concessions from employers. By the end of the nineteenth century, courts generally held that strikes for higher wages or shorter workdays were legal.

Despite the decline of the labor conspiracy theory, unions faced other legal challenges to their existence. The labor INJUNCTION and prosecution under antitrust laws became powerful weapons for employers who were involved in labor disputes. In an 1896 case, Vegelahn v. Guntner, 167 Mass. 92, 44 N.E. 1077, the highest court in Massachusetts upheld an injunction that forbade peaceful picketing outside the employer's premises.

The first national labor federation to remain active for more than a few years was the Noble Order of the Knights of Labor. It was established in 1869 and had set as goals the eight-hour workday, equal pay for equal work, and the abolition of child labor. The Knights of Labor grew to 700,000 members by 1886 but went into decline that year with a series of failed strikes. By 1900, it had disappeared.

Labor unions nevertheless gained strength in 1886 with the formation of the AMERICAN FEDERATION OF LABOR (AFL). Composed of 25 national trade unions and numbering over 316,000 members, the AFL was a loose confederation of autonomous unions, each with exclusive rights to deal with the workers and employers in its own field. The AFL concentrated on pursuing achievable goals such as higher wages and shorter hours, and it renounced identification with any political party or movement. Members were encouraged to support politicians who were friendly to labor, whatever their party affiliation.

Following the passage of the SHERMAN ANTI-TRUST ACT in 1890 (15 U.S.C.A. §§ 1 et seq.), which prohibited combinations in restraint of trade, courts punished and enjoined labor practices that were considered wrongful. In the Danbury Hatters case (Loewe v. Lawlor, 208 U.S. 274, 28 S. Ct. 301, 52 L. Ed. 488 [1908]), the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the application of the act to an appeal that involved a labor publication for a general boycott of named nonunion employers. In 1911, in Gompers v. Buck's Stove & Range Co., 221 U.S. 418, 31 S. Ct. 492, 55 L. Ed. 797, the Court upheld an injunction against a union that had placed the name of the employer on the AFL "We Don't Patronize" list, which was a call for a boycott of the employer.

Opposition to labor unions was particularly intense during the late nineteenth century. Several unsuccessful strikes in the 1890s demonstrated the power of companies to crush unions. In 1892, steelworkers struck against the Carnegie Steel Company's Homestead, Pennsylvania, plant. The company hired private guards to protect the plant, but violence broke out. The strike failed, and most of the workers quit the union and returned to work. In 1894, members of the American Railway Union struck the Pullman Palace Car Company, which made railroad cars. The federal government sent in troops to end the strike.

Despite these setbacks, labor unions gradually increased their political power at the federal level. In 1914, Congress enacted the CLAYTON ACT, sections 6 (15 U.S.C.A. § 7) and 20 (29 U.S.C.A. § 52), declaring that human labor was not to be considered an article of commerce and that the existence of unions was not to be considered a violation of ANTITRUST LAWS. In addition, the act prohibited federal courts from issuing injunctions in labor disputes except to prevent irreparable injury to property. This prohibition was absolute when peaceful picketing and boycotts were involved.

Employers had better success fighting unions by using the so-called YELLOW-DOG CONTRACT. This agreement required a prospective employee to state that he or she was not a member of a union and would not become one. Although some states enacted laws that prohibited employers from requiring employees to sign this type of contract, the U.S. Supreme Court declared such statutes unconstitutional as an infringement of freedom of contract (Coppage v. Kansas, 236 U.S. 1, 35 S. Ct. 240, 59 L. Ed. 441 [1915]).

By 1920, trade unions had over five million members. During the 1920s, however, the TRADE UNION movement suffered a decline, precipitated in part by a severe economic depression in 1921-22. Unemployment rose, and competition for jobs became intense. By 1929, union membership had dropped to 3.5 million.

The Great Depression of the 1930s caused more unemployment and a further decline in union membership. Unions responded with numerous strikes, but few were successful. Despite these reverses, the legal position of unions was enhanced during the 1930s. In 1932, Congress passed the NORRIS-LAGUARDIA ACT (29 U.S.C.A. §§ 101 et seq.), which declared yellow-dog contracts to be contrary to public policy and stringently limited the power of federal courts to issue injunctions in labor disputes. In cases in which an injunction still might be issued, the act imposed strict procedural limitations and safeguards in order to prevent more instances of abuses by the courts. The Norris-LaGuardia Act effectively ended "government by injunction" and has remained a fundamental law in labor disputes.

During the 1930s, the AFL itself was in turmoil over the aspirations of the labor movement. The trade unions that dominated the AFL were composed of skilled workers who opposed organizing the unskilled or semiskilled workers on the manufacturing production line. Several unions rebelled at this refusal to organize and formed the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO). The CIO aggressively organized millions of workers who labored in automobile, steel, and rubber plants. In 1938, unhappy with this effort, the AFL expelled the unions that formed the CIO. The CIO then formed its own organization, changed its name to Congress of Industrial Organizations, and elected John L. Lewis, of the United Mine Workers, as its first president.

U.S. labor relations were dramatically altered in 1935 with the passage of the National Labor Relations Act, also known as the WAGNER ACT (29 U.S.C.A. §§ 151 et seq.). For the first time, labor unions were given legal rights and powers under federal law. The act guaranteed the right of COLLECTIVE BARGAINING, free from employer domination or influence. It made it an UNFAIR LABOR PRACTICE for an employer to interfere with employees in the exercise of their right to bargain collectively; to interfere with or to influence unions; to discriminate in hiring or firing because of an employee's union membership; to discriminate against an employee who avails himself or herself of legal rights; or to refuse to bargain collectively.

The Wagner Act also established the NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD, which has the power to investigate employees' complaints and to issue cease and desist orders. If an employer were to defy such an order, the board may ask a federal court of appeals for an enforcement order, or it could ask the court to review the cease-and-desist order. The board could conduct elections to determine which union should represent the employees in a bargaining unit and certify the union as their agent, and it could designate the bargaining unit.

The heart of the Wagner Act was section 7 (29 U.S.C.A. § 157), which stated the public policy that workers have the right to engage in self-organization, in collective bargaining, and in concerted activities in support of self-organization and collective bargaining. Armed with these rights, unions grew in membership and strength during the late 1930s and through WORLD WAR II.

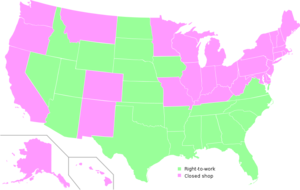

A number of states reacted negatively to these legal changes by enacting laws that sought to restrict and lessen the power of unions. An antiunion backlash developed after World War II, when strikes against the automobile industry and other large corporations reached record numbers. This reaction culminated in the passage of the LABOR-MANAGEMENT RELATIONS ACT of 1947, also known as the TAFT-HARTLEY ACT (29 U.S.C.A. §§ 141 et seq.). The Taft-Hartley Act amended section 7 of the Wagner Act, affirming the rights that had been formulated in 1935 but providing that workers shall have the right to refrain from any of the listed activities. Whereas the Wagner Act listed only employers' unfair labor practices, Taft-Hartley added unions' unfair labor practices. The act created the FEDERAL MEDIATION AND CONCILIATION SERVICE, which provides a method for addressing strikes that create a national emergency. It also banned the CLOSED SHOP, which requires an employer to hire only union members and to discharge any employee who drops union membership. Taft-Hartley effectively replaced the Wagner Act as the basic federal statute regulating labor relations.

In 1955, the AFL and CIO merged into a single organization, the AFL-CIO. The staunchly anti-communist AFL agreed to the merger only after the CIO had purged its organization of communists and supporters of communist ideals. George Meany was appointed the first president of the new organization.

In 1959, Congress enacted the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act, also

known as the LANDRUM-GRIFFIN ACT (29 U.S.C.A. §§ 401 et seq.). Title VII of the act contains many amendments to the Taft-Hartley Act, of which two are especially important. First, Landrum-Griffin made peaceful picketing of organizational or recognitional objectives illegal under certain circumstances. Second, it closed loopholes in the provisions of Taft-Hartley that forbadesecondary boycotts.

Other sections of Landrum-Griffin provided for a bill of rights for union members, financial disclosure requirements for unions and their officers, and safeguards in union elections. All of these matters concerned internal union practices, strongly suggesting that union corruption had become a problem. In fact, a 1957 congressional investigation of the Teamsters union had uncovered widespread corruption and had much to do with the introduction of these new statutory provisions.

Labor unions continued to thrive in the 1960s, as a robust economy relied on a large manufacturing industry to maintain growth. Although no comprehensive union legislation was enacted during that decade, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 (42 U.S.C.A. §§ 2000a et seq.), made an important contribution to national labor policy. The act declared it an unfair labor practice for an employer or union to discriminate against a person by reason of race, religion, color, sex, or national origin. Administration of this provision is vested in the EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION (EEOC). Under the CIVIL RIGHTS ACT, if the EEOC is unable to achieve voluntary compliance, the person allegingdiscrimination is authorized to bring a civil action in federal district court. The 1972 amendment gave the EEOC the right to bring such an action. The effect of the law has been to desegregate many trade unions that maintained an all-white membership policy.

The union movement considerably improved working conditions for migrant workers in the late 1960s and the 1970s. The UNITED FARM WORKERS, under the leadership of CESAR CHAVEZ, led successful boycotts and strikes against California growers, most notably against the wine-grape growers.

Many unions suffered, however, with an economic downturn in the 1970s and 1980s, and with the decline of well-paying manufacturing jobs. Automation of industrial processes reduced the number of workers who were required on assembly lines. In addition, many U.S. companies moved either to states that did not have a strong union background or to developing countries where labor costs were significantly lower. Union members became more concerned about job security than about higher wages, particularly in the manufacturing industry, and they agreed to concede salary and benefit givebacks. In return, unions sought greater labor-management cooperation and a larger voice in the allocation of jobs and in the work environment.

Union membership has also declined in response to a shift from blue-collar manufacturing jobs to white-collar service and technology jobs. By the end of 2002, just 13.2 percent of the U.S. workforce claimed union membership, compared with a high of 34.7 percent in 1954.

FURTHER READINGS

Bagchi, Aditi. 2003. "Unions and the Duty of Good Faith In Employment Contracts." Yale Law Journal 112 (May).

Bureau of Labor Statistics site. Available online at <www.bls.gov> (accessed April 21, 2003).

CROSS-REFERENCES

Child Labor Laws; Craft Union; Employment Law; Hoffa, James Riddle; Labor Law; Right-To-Work Laws.

Additional topics

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationFree Legal Encyclopedia: Labor Department - Employment And Training Administration to Legislative Power