Clarence Earl Gideon Trials: 1961 & 1963

Gideon Appeals

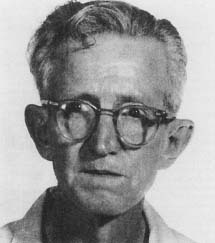

Defendant: Clarence Earl Gideon

Crime Charged: Breaking and entering

Chief Defense Lawyers: First trial: None; Second trial: W. Fred Turner

Chief Prosecutor: First trial: William E. Harris; Second trial: J. Frank Adams, J. Paul Griffith, and William E. Harris

Judge: Robert L. McCrary, Jr.

Place: Panama City, Florida

Dates of Trials: First trial: August 4, 1961;Second trial: August 5, 1963

Verdict: First trial: Guilty; Second trial: Not guilty

Sentence: First trial: 5 years imprisonment

SIGNIFICANCE: One man, without benefit of wealth, privilege, or education, went up against the entire legal establishment, arguing that his constitutional rights had been violated. In doing so, he brought about an historic change in American trial procedure: all felony defendants are entitled to legal representation, irrespective of the crime charged, and courts are to appoint an attorney if a defendant is too poor to hire one.

At eight o'clock on the morning of June 3, 1961, a patrolling police officer in Panama City, Florida, noticed that the door of the Bay Harbor Poolroom was open. Stepping inside, he saw that a cigarette machine and jukebox had been burglarized. Eyewitness testimony led to the arrest of Clarence Gideon, a 51-year-old drifter who occasionally helped out at the poolroom. He vehemently protested his innocence but two months later was placed on trial at the Panama City Courthouse. No one present had any inkling that they were about to witness history in the making.

As the law then stood, Gideon, although indigent, was not automatically entitled to the services of a court-appointed defense lawyer. A 1942 Supreme Court decision, Betts v. Brady, extended this right only to those defendants facing a capital charge. Many states did, in fact, exceed the legal requirements and provide all felony defendants with counsel, but not Florida. Judge Robert L. McCrary, Jr. did his best to protect Gideon's interests when the trial opened August 4, 1961, but he clearly could not assume the role of advocate; that task was left to Gideon himself. Under the circumstances Gideon, a man of limited education but immense resourcefulness, performed as well as could be expected, but he was hardly the courtroom equal of Assistant State Attorney William E. Harris, who scored heavily with the testimony of Henry Cook.

This young man claimed to have seen Gideon inside the poolroom at 5:30 on the morning of the crime. After watching Gideon for a few minutes through the window, Cook said, the defendant came out clutching a pint of wine in his hand, then made a telephone call from a nearby booth. Soon afterward a cab arrived and Gideon left.

In cross-examination Gideon sought to impugn Cook's reasons for being outside the bar at that time of the morning. Cook replied that he had "just come from a dance, down in Apalachicola—stayed out all night." A more experienced cross-examiner might have explored this potentially fruitful line of questioning, but Gideon let it pass and lapsed into a vague and argumentative discourse.

Eight witnesses testified on the defendant's behalf. None proved helpful and Clarence Gideon was found guilty. The whole trial had lasted less than one day. Three weeks later Judge McCrary sentenced Gideon to the maximum: five years imprisonment.

Clarence Earl Gideon argued that his constitutional rights were denied when he was refused an attorney.

Clarence Earl Gideon argued that his constitutional rights were denied when he was refused an attorney.

Additional topics

- Communist Party of the United States v. Subversive Activities Control Board - Significance

- Cheryl Christina Crane Inquest: 1958 - Tale Of Star-crossed Lovers, Cheryl's Statement Introduced

- Clarence Earl Gideon Trials: 1961 1963 - Gideon Appeals

- Other Free Encyclopedias

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationNotable Trials and Court Cases - 1954 to 1962