Plessy v. Ferguson: 1896

Appellant: Homer A. Plessy

Respondent: New Orleans Criminal District Court Judge J.H. Ferguson

Appellant's Claim: That Louisiana's law requiring blacks to ride in separate railroad cars violated Plessy's right to equal protection under the law

Chief Defense Lawyer: M.J. Cunningham

Chief Lawyers for Appellant: F.D. McKenney and S.F. Phillips

Justices: Supreme Court Justices David J. Brewer, Henry B. Brown, Stephen J. Field, Melville W. Fuller, Horace Gray, John Marshall Harlan, Rufus W. Peckham, George Shiras and Edward D. White

Place: Washington, D.C.

Date of Decision: May 18, 1896

Decision: That laws providing for "separate but equal" treatment of blacks and whites were constitutional

SIGNIFICANCE: The Supreme Court's decision effectively sanctioned discriminatory state legislation. Plessy was not fully overruled until the 1950s and 1960s, beginning with Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

In the years following the Supreme Court's 1875 decision in U.S. v. Cruikshank (see separate entry), which limited the federal government's ability to protect blacks' civil rights, many states in the South and elsewhere enacted laws discriminating against blacks. These laws ranged from restrictions on voting, such as literacy tests and the poll tax, to requirements that blacks and whites attend separate schools and use separate public facilities.

On June 7, 1892, Homer A. Plessy bought a train ticket for travel from New Orleans to Covington, Louisiana. Plessy's ancestry was one-eighth black and the rest white, but under Louisiana law he was considered to be black and was required to ride in the blacks-only railroad car. Plessy sat in the whites-only railroad car, refused to move, and was promptly arrested and thrown into the New Orleans jail.

Judge John H. Ferguson of the District Court of Orleans parish presided over Plessy's trial for the crime of having refused to leave the whites-only car, and Plessy was found guilty. Plessy's conviction was upheld by the Louisiana Supreme Court, and Plessy appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court for an order forbidding Louisiana in the person of Judge Ferguson from carrying out the conviction.

Ferguson was represented by Louisiana Attorney General M.J. Cunningham and Plessy by F.D. McKenney and S.F. Phillips. On April 13, 1896, Plessy's lawyers argued before the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., that Louisiana had violated Plessy's Fourteenth Amendment right to equal protection under the law. Attorney General Cunningham argued that the law merely made a distinction between blacks and whites, but didn't necessarily treat blacks as inferiors, since theoretically the law provided for "separate but equal" railroad car accommodations.

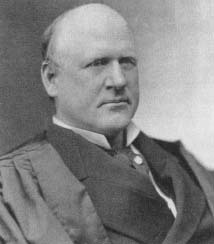

John Marshall Harlan, the only dissenting justice, argued that, "Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens." (Courtesy, Library of Congress)

John Marshall Harlan, the only dissenting justice, argued that, "Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens." (Courtesy, Library of Congress)

On May 18, 1896, the Court issued its decision. It upheld the Louisiana law:

A statute which implies merely a legal distinction between the white and colored races—a distinction which is founded in the color of the two races, and which must always exist so long as white men are distinguished from the other race by color—has no tendency to destroy the legal equality of the two races.

Therefore, the Court affirmed Plessy's sentence, namely a $25 fine or 20 days in jail. Further, the Court endorsed the "separate but equal" doctrine, ignoring the fact that blacks had practically no power to make sure that their "separate" facilities were "equal" to those of whites. In the years to come, black railroad cars, schools and other facilities were rarely as good as those of whites. Only Justice John Marshall Harlan dissented from the Court's decision. Harlan's dissent was an uncannily accurate prediction of Plessy's effect:

Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.… In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott case.… The present decision, it may well be apprehended, will not only stimulate aggressions, more or less brutal and irritating, upon the admitted rights of colored citizens, but will encourage the belief that it is possible, by means of state enactments, to defeat the beneficient purposes which the people of the United States had in view when they adopted the recent amendments of the Constitution.

It was not until the 1950s and the 1960s that the Supreme Court began to reverse Plessy. In the landmark 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education, the Court held that separate black and white schools were unconstitutional, and later cases abolished the separate but equal doctrine in other areas affecting civil rights as well.

—Stephen G. Christianson

Suggestions for Further Reading

Kull, Andrew. The Color-Blind Constitution. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Olsen, Otto H. The Thin Disguise: Turning Point in Negro History. New York: Humanities Press, 1967.

Additional topics

- Robert Buchanan Trial: 1893 - Grisly Demonstration

- Plessy v. Ferguson - Significance, "separate But Equal", Further Readings

- Other Free Encyclopedias

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationNotable Trials and Court Cases - 1883 to 1917