Temperance Movement

The TEMPERANCE MOVEMENT in the United States first became a national crusade in the early nineteenth century. An initial source of the movement was a groundswell of popular religion that focused on abstention from alcohol. Evangelical preachers of various Christian denominations denounced drinking alcohol as a sin. People who drank, they claimed, lost their faith in God and ceased to observe the teachings of Jesus.

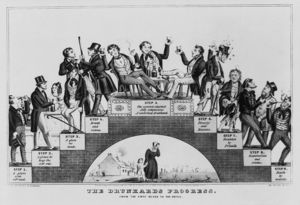

Other supporters of the first temperance movement objected to alcohol's destructive effects on individuals, communities, and the nation as a whole. According to these activists, the consumption of alcohol was responsible for many personal and societal problems, including unemployment, absenteeism in the workplace, and physical violence. Scores of short stories and books published in the mid-nineteenth century described in dramatic detail the abuse suffered by the families of alcoholics. Alcoholics were characterized as dangerous to themselves, their families, and even their nation's security. In the words of temperance advocate Lyman Beecher, a drunk electorate would "dig the grave of our liberties and entomb our glory."

The temperance movement was marked by an undercurrent of ethnic and religious hostility. Some of the first advocates were people of Anglo-Saxon heritage who associated alcohol with the growing number of Catholic immigrants from Ireland and the European continent. Supposedly, the Catholics were loud and boisterous as a result of too much drinking.

Most of the first temperance advocates were sincerely concerned for the welfare of others, however, and were not motivated by such faulty perceptions. The public's rate of alcohol consumption was, in fact, increasing steadily during the nineteenth century, and the reformers saw the banishment of alcohol not as a punishment but as necessary to an orderly, safe, and prosperous society. Despite its good intentions, the first movement splintered. The largest rift occurred between a minority of abolitionists, who favored the promotion of total abstinence from alcohol, and the majority of reformers, who favored only abstinence from hard liquor.

Although it lacked cohesion, the first temperance movement yielded some legislative reforms. In 1846, Maine became the first state to enact a law prohibiting liquor consumption. Twelve other states followed suit, but the laws were difficult to enforce, and public support for the laws quickly waned. By 1868 Maine was the only state left with a liquor PROHIBITION law, and the temperance movement appeared to have come and gone.

Carry Nation, a well-known prohibitionist, holds a Bible and a hatchet. Nation often used a hatchet to smash liquor bottles and furniture in saloons.

Groups such as the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Anti-Saloon League were at the forefront of the onslaught on alcohol. Members of these groups spoke publicly in favor of Prohibition and lobbied elected officials for laws banning the consumption of alcohol. Some of the more active members disrupted business at saloons and liquor stores. One of the most visible prohibitionists, Carry Nation, used a hatchet to smash liquor bottles and break furniture in saloons.

In the 1870s some prohibitionists began to form political parties and nominate candidates for public office. Leaders in the so-called Progressive movement were instrumental in the resurgence of the temperance movement. The Progressives called for sweeping governmental controls in response to perceived social crises, and they began to promote the abolition of alcohol as part of a plan to clean up cities and eliminate poverty. By the time WORLD WAR I began in 1914, an increasing number of politicians were advocating a ban on alcohol, and the conservation efforts for the war gave the temperance movement additional momentum.

Congress enacted the Lever Act of 1917 (40 Stat. 276) to outlaw the use of grain in the manufacture of alcoholic beverages, and many state and local governments passed laws prohibiting the distribution and consumption of alcohol. Two years later, the states ratified the EIGHTEENTH AMENDMENT to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the manufacture, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages in the United States. The complete ban on alcohol was put into effect by the Volstead Act (41 Stat. 305). President WOODROW WILSON vetoed the act, but Congress overrode the VETO and the United States became officially dry in January 1920.

The effect of Prohibition was to drive drinking underground. Saloons were replaced by speakeasies, hidden drinking places that, in some areas, were tolerated by local police. The more enterprising individuals set up homemade stills to produce alcohol for their own consumption. Others turned to bootlegging, or the illegal sale of alcohol. Prices on the black market were markedly higher than they had been prior to Prohibition, and gangsters used violence to acquire and maintain control over the highly profitable bootlegging business. Bootlegging was so profitable because so many people wanted to drink alcohol. Federal, state, and local law enforcement officials found themselves at war not only with gangsters, but with the general public as well.

Popular support for Prohibition quickly waned after the Eighteenth Amendment was passed, but it took thirteen years to end it. HERBERT HOOVER, who served as president from 1929 to 1933, supported Prohibition, calling it "an experiment noble in purpose." Hoover was defeated in his bid for reelection, however, and in 1933 President FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT called for an amendment to the Volstead Act that would legalize light wine and beer consumption. The bill passed quickly and received widespread public support, and Congress set about the task of repealing Prohibition. On December 5, 1933, the TWENTY-FIRST AMENDMENT to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, and the "noble experiment" was dismantled.

FURTHER READINGS

Blocker, Jack S. 1989. American Temperance Movements: Cycles of Reform. Boston: Twayne.

Pegram, Thomas R. 1998. Battling Demon Rum: The Struggle for a Dry America, 1800–1933. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee.

Szymanski, Ann-Marie E. 2003. Pathways to Prohibition: Radicals, Moderates, and Social Movement Outcomes. Durham, N.C.: Duke Univ. Press.

CROSS-REFERENCES

Additional topics

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationFree Legal Encyclopedia: Taking at sea to Tonkin Gulf Resolution