Police Corruption and Misconduct

History, Contemporary Problems, Further Readings

The violation of state and federal laws or the violation of individuals' constitutional rights by police officers; also when police commit crimes for personal gain.

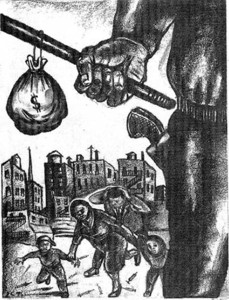

Police misconduct and corruption are abuses of police authority. Sometimes used interchangeably, the terms refer to a wide range of procedural, criminal, and civil violations. Misconduct is the broadest category. Misconduct is "procedural" when it refers to police who violate police department rules and regulations; "criminal" when it refers to police who violate state and federal laws; "unconstitutional" when it refers to police who violate a citizen's CIVIL RIGHTS; or any combination thereof. Common forms of misconduct are excessive use of physical or DEADLY FORCE, discriminatory arrest, physical or verbal harassment, and selective enforcement of the law.

Police corruption is the abuse of police authority for personal gain. Corruption may involve profit or another type of material benefit gained illegally as a consequence of the officer's authority. Typical forms of corruption include BRIBERY, EXTORTION, receiving or fencing stolen goods, and selling drugs. The term also refers to patterns of misconduct within a given police department or special unit, particularly where offenses are repeated with the acquiescence of superiors or through other ongoing failure to correct them.

Safeguards against police misconduct exist throughout the law. Police departments themselves establish codes of conduct, train new recruits, and investigate and discipline officers, sometimes in cooperation with civilian complaint review boards which are intended to provide independent evaluative and remedial advice. Protections are also found in state law, which permits victims to sue police for damages in civil actions. Typically, these actions are brought for claims such as the use of excessive force ("police brutality"), false arrest and imprisonment, MALICIOUS PROSECUTION, and WRONGFUL DEATH. State actions may be brought simultaneously with additional claims for constitutional violations.

Through both criminal and civil statutes, federal law specifically targets police misconduct. Federal law is applicable to all state, county, and local officers, including those who work in correctional facilities. The key federal criminal statute makes it unlawful for anyone acting with police authority to deprive or conspire to deprive another person of any right protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States (Section 18 U.S.C. § 241 [2000]). Another statute, commonly referred to as the police misconduct provision, makes it unlawful for state or local police to engage in a pattern or practice of conduct that deprives persons of their rights (42 U.S.C.A. 14141 [2000]).

Additionally, federal law prohibits discrimination in police work. Any police department receiving federal funding is covered by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. § 2000d) and the Office of Justice Programs statute (42 U.S.C. § 3789d[c]), which prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, and religion. These laws prohibit conduct ranging from racial slurs and unjustified arrests to the refusal of departments to respond to discrimination complaints.

Because neither the federal criminal statute nor the civil police misconduct provision provides for lawsuits by individuals, only the federal government may bring suit under these laws. Enforcement is the responsibility of the JUSTICE DEPARTMENT. Criminal convictions are punishable by fines and imprisonment. Civil convictions are remedied through injunctive relief, a type of court order that requires a change in behavior; typically, resolutions in such cases force police departments to stop abusive practices, institute types of reform, or submit to court supervision.

Private litigation against police officers or departments is difficult. Besides time and expense, a significant hurdle to success is found in the legal protections that police enjoy. Since the late twentieth century, many court decisions have expanded the powers of police to perform routine stops and searches. Plaintiffs generally must prove willful or unlawful conduct on the part of police; showing mere NEGLIGENCE or other failure of due care by police officers often does not suffice in court.

Most problematically of all for plaintiffs, police are protected by the defense of immunity—an exemption from penalties and burdens that the law generally places on other citizens. This IMMUNITY is limited, unlike the absolute immunity enjoyed by judges or legislators. In theory, the defense allows police to do their job without fear of REPRISAL. In practice, however, it has become increasingly difficult for individuals to sue law enforcement officers for damages for allegedly violating their civil rights. U.S. Supreme Court decisions have continually asserted the general rule that officers must be given the benefit of the doubt that they acted lawfully in carrying out their day-to-day duties, a position reasserted in Saucier v. Katz, 533 U.S. 194, 121 S. Ct. 2151, 150 L. Ed. 2d 272 (2001).

CROSS-REFERENCES

Civil Rights; Conspiracy; Constitutional Law; Discrimination; Fourth Amendment; Immunity; Ku Klux Klan; Pinkerton Agents; Privacy.

Additional topics

- Police and Private Guards

- Police - Further Readings

- Police Corruption and Misconduct - History

- Police Corruption and Misconduct - Contemporary Problems

- Police Corruption and Misconduct - Further Readings

- Other Free Encyclopedias

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationFree Legal Encyclopedia: Plc (public limited company) to Prerogative of mercy