George Franklin Trial: 1990-91

Daughter Is Star Witness At Father's Trial

The trial opened in late October 1990, and Franklin-Lipsker became the star wit-.-ness. The prosecution's case revolved almost totally on her account based on the resurfacing of her repressed memories. Leading psychiatrists and psychologists testified on behalf of both the prosecution and defense. The prosecution witnesses explained the theory of the repression of traumatic memories; the defense witnesses argued that Franklin-Lipsker did not fit the profile of those who had such memories, and, indeed, called into question the accuracy of such memories in any event. The defense also argued that all of the facts to which Franklin-Lipsker testified had been reported in the papers; she therefore could have known what had happened without being an eye-witness to the murder.

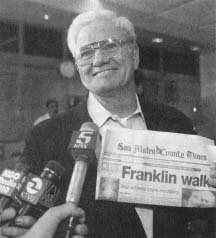

George Franklin as he was released from jail.

George Franklin as he was released from jail.

Trial judge Thomas McGinn Smith prevented the defense from introducing newspaper accounts that mentioned the facts that Franklin-Lipsker revealed. However, he did allow the admission of what some would call circumstantial evidence. When Franklin-Lipsker went to visit her father in prison before the trial and asked him to tell the truth, Franklin had said nothing, instead pointing to a prison sign that warned inmates that officials might monitor their conversations. Franklin's silence, said prosecutor Elaine Tipton, in the face of this accusation, was "worth its weight in gold" as an implied admission of guilt.

On November 30, 1990, the jury found Franklin guilty of Susan's murder, although the prosecution had not produced any physical evidence to connect houghhim with theher death. prosecutionThe conviction rested almost totally on Franklin-Lipsker's testimony, despite her estrangement from him and the psychologists who challenged the veracity of her claims. On January 29, 1991, Judge Smith sentenced Franklin to life imprisonment, the maximum sentence possible under the law at the time of the 1969 murder. However, in 1995, a federal appeals court overturned the conviction, finding that Judge Smith should have allowed Franklin to challenge his daughter's testimony by being able to introduce the newspaper articles as evidence. The court also found that using Franklin's silence as evidence of an admission of guilt violated his constitutional right to remain silent. Finally, the court noted that the entire subject of repressed memory was a highly controversial one whose accuracy was still subject to debate. Franklin later sued his daughter and the psychologists who had testified against him for conspiracy to present false testimony, but the courts ultimately rejected this suit.

While memories of past events are often used as evidence in civil and criminal trials, the heavy reliance on repressed memory in the Franklin case was unique in American criminal law. Trial courts had long recognized that memories could be faulty, especially when they were of events from far in the past. The federal appeals court here found that the repressed memories of Franklin-Lipsker were no different from other types of memories, and it criticized the trial court for refusing to let the defense test these memories, as it would have been able to test any others.

After being imprisoned for six years, George Franklin was released from jail when his conviction was overturned.

—Buckner F. Melton, Jr.

Suggestions for Further Reading

MacLean, Harry N. Once Upon a Time: A True Story of Memory, Murder, and the Law. New York: HarperCollins, 1993.

Terr, Lenore. Unchained Memories: True Stories of Traumatic Memories, Lost and Found. New York: Basic Books, 1994.

Additional topics

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationNotable Trials and Court Cases - 1989 to 1994George Franklin Trial: 1990-91 - Daughter Goes To Police, Daughter Is Star Witness At Father's Trial