Haymarket Trial: 1886

Chicago: Hotbed Of Radicalism, Police Arrest Eight Anarchists, Suggestions For Further Reading

Defendants: George Engel, Samuel Fielden, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, Oscar Neebe, Albert Parsons, Michael Schwab, and August Spies

Crime Charged: Murder

Chief Defense Lawyers: William P. Black, William A. Foster, Moses Salomon, and Sigismund Zeisler

Chief Prosecutor: Julius S. Grinnell

Judge: Joseph E. Gary

Place: Chicago, Illinois

Dates of Trial: June 21-August 20, 1886

Verdict: Guilty

Sentence: Death by hanging for all but Neebe, who was sentenced to prison for 15 years

SIGNIFICANCE: The Haymarket Riot was one of the most famous confrontations between the growing labor movement and the conservative forces of industry and government. Eight police officers were killed in a bomb explosion during the Haymarket affair. The resulting public backlash against the labor movement was a serious setback for the unions and their efforts to improve industrial working conditions.

After the Civil War, the United States experienced a period of unparalleled industrial growth that lasted for decades. It was a time when men became famous building new industries and businesses, establishing great corporate empires in the process. Among them were John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, which dominated the new petroleum industry; Andrew Carnegie's Carnegie Steel (later U.S. Steel), which revolutionized open-hearth steel technology and became the industry leader; and Marshall Field, named for its founder, which changed retailing from a multitude of mom-and-pop operations into an industry dominated by a handful of giants. However, the wealthy few who controlled this industrial development and its riches did not share their gains with the workers who made their terrific success possible.

By the 1880s, America's rapid industrialization had not yet produced any significant change in the legal relationship between workers and employers. Under the common law, inherited from England, any worker or laborer was free to negotiate individually with his employer concerning his wages, working hours and conditions, and other benefits. This may have been fine for the medieval English guilds whose practices shaped this aspect of the common law, but it was hopelessly out of touch with the realities of the modern industrial workplace. By the 1880s, American business was dominated by companies that employed large numbers of workers in factories, stores, mills, and other workplaces.

An individual worker's right to "negotiate" his wages was thus meaningless. Immigrants from abroad and American migration from the farms to the cities swelled the labor force available to industrial employers. Any worker who complained about his or her wages, sought better hours, or wanted benefits such as sick leave or compensation for on-the-job injuries could be easily replaced.

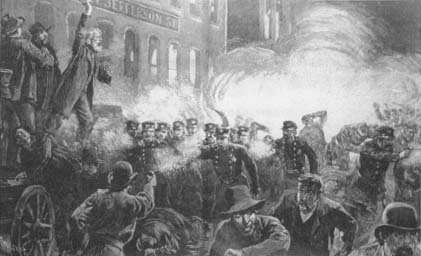

Police, U.S. military soldiers and firefighters attempting to control the chaos brought on by the Haymarket riots,

Police, U.S. military soldiers and firefighters attempting to control the chaos brought on by the Haymarket riots,

The only way for workers to improve their lives was to band together, "to unionize," so that one organization representing the combined workforce could compel management to make concessions. Naturally, companies resisted, and relations between the budding union movement and management became strained and often violent. Because unionists saw the government as an ally of big business in oppressing workers, many unionists were attracted to the political ideology of anarchism, which sought to do away with government.

Additional topics

- Holden v. Hardy - Significance, Utah Limits The Miner's Workday, "a Progressive Science", Miners And Bakers

- Harry Thaw Trials: 1907-08 - Evelyn Nesbit Comes To New York, Thaw Is Tried For Murder, Suggestions For Further Reading

- Haymarket Trial: 1886 - Chicago: Hotbed Of Radicalism

- Haymarket Trial: 1886 - Police Arrest Eight Anarchists

- Haymarket Trial: 1886 - Suggestions For Further Reading

- Other Free Encyclopedias

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationNotable Trials and Court Cases - 1883 to 1917