Henry Flipper Court-Martial: 1881

The Court-martial

The court-martial convened at Fort Davis on September 15, 1881, but was suspended until November 1 to allow Flipper time to obtain counsel. Flipper was formally charged with embezzling a total of $3,791.77—most of which he had repaid by that time—and also with conduct unbecoming an officer. As always since he had become part of the army, Flipper found himself confronting an all-white world, but his attorney, Capt. Merritt Barber, mounted a solid defense. On the charge of embezzlement, he argued that under the governing military law, it had to be proven that the individual charged engaged in "intentional, wrongful, and willful conversion of public money to his own use and benefit." This, Barber noted, the prosecution had utterly failed to demonstrate and that at most Flipper was guilty of poor bookkeeping and records maintenance. To support the claim that Flipper had from the beginning planned to repay the missing sum, he argued that Flipper was expecting a check for $2,500 from a New York publisher, the royalties for his book about his time at West Point. One can only imagine the effect this must have had on a panel of white officers: a 25-year-old African American earning royalties from a book describing his mistreatment at the hands of his fellow cadets and officers!

The second charge, conduct unbecoming an officer, involved such actions as writing a false check (in an attempt to cover some of the missing funds), lying to his superior officer, and signing false reports. In fact, Flipper had done all of these, but his defense attorney argued that there were extenuating circumstances: the so-called false check? Flipper had never tried to use it in any transaction—he had only displayed it to his superior. If Flipper lied to this same superior, it was only because this man had not given him the expected guidance and support; therefore, argued Barber—turning conventional reasoning inside our—Flipper had employed minor untruths in a misguided attempt to maintain his image of a West Point officer. As for the false reports, the lawyer argued that behind this charge was the premise that he had embezzled the money for his own purposes—and there was no evidence of that.

On the broader issue of what constituted "conduct unbecoming an officer," the defense attorney referred to two fairly recent court-martials where officers had been charged with this offense. In both cases, the officers were let off on the ground that their actions had not been "prejudicial to good order and military discipline." Captain Barber argued that the same could be said of Flipper's actions. In his summation, Barber went even further, employing the flowery rhetoric typical of the day:

May we not therefore ask this court to take into consideration, the unequal battle my client has to wage, poor, naked, and practically alone, with scarce an eye of sympathy or a word to cheer, against all the resources of zealous numbers, official testimony, official position, experience and skill, charged with all the ammunition which the government could furnish from Washington to Texas, and may we not trust that this court will throw around him the mantle of its charity, if any errors are found, giving him the benefit of every doubt… and giving him your confidence that the charity you extend to him so generously will be as generously redeemed by his future record in the service.

What was most revealing here, as well as through the entire trial, is that there is no explicit reference to Flipper's being an African American. In any case, realizing they had no evidence to convict Flipper of embezzlement, the court returned a verdict of not guilty on that charge, but they did find him guilty of conduct unbecoming an officer. The sentence was that he be dismissed from the service.

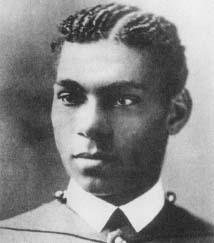

Lieutenant Henry Flipper, the first African American to graduate from West Point.

Lieutenant Henry Flipper, the first African American to graduate from West Point.

At that time, an officer could not be dismissed as a result of a court-martial until after the sentence had been reviewed by the president of the United States. Flipper's case passed up to the president through the normal channels of review, and the judge advocate general of the U.S. Army, David G. Swain, did in fact recommend that the guilty verdict be "mitigated to a lesser degree of punishment." President Chester Alan Arthur, however, simply approved the original judgment and sentence, and Flipper was dishonorably discharged from the army in 1882.

Additional topics

- Henry Flipper Court-Martial: 1881 - Flipper's Later Fate

- Henry Flipper Court-Martial: 1881 - A Different Kind Of Trial

- Other Free Encyclopedias

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationNotable Trials and Court Cases - 1833 to 1882Henry Flipper Court-Martial: 1881 - A Different Kind Of Trial, The Court-martial, Flipper's Later Fate, Suggestions For Further Reading