U.S. v. Cruikshank: 1875

Southern Racism Makes A Comeback

Despite the new legal protection for ex-slaves, as Southern states were readmitted to the Union and the occupation forces went home, the old ways returned in new guises. Landowners no longer owned slaves, but the practice of sharecropping effectively kept blacks tied to the land and subservient to whites. Southern states passed "Jim Crow" laws enforcing the separation of blacks from whites in public accommodations. What states couldn't do in public, Southern whites did in private. The Ku Klux Klan developed as an instrument of terror to enforce white supremacy. Hard-won black liberties began to slip away.

As Congress' act of 1870 demonstrated, however, the North would not give up without a fight. Three years later, matters came to a head. On April 13, 1873, a Southern mob in Grant Parish, Louisiana numbering nearly 100 people lynched two African-American men, Levi Nelson and Alexander Tillman. Apparently Nelson and Tillman had tried to vote in a local election against the wishes of white residents. Approximately 80 people in the lynch mob were indicted for violations of federal law and 17 were eventually brought to trial, including one William J. Cruikshank. The U.S. attorney in charge, J.R. Beckwith, charged each of them with 16 violations of the 1870 law. The most important charge was violating the victims' "right and privilege peaceably to assemble together."

Cruikshank and the others, however, were not charged with murder. Nelson and Tillman's murder was a Louisiana state offense, not a violation of the federal law, and the Louisiana authorities didn't prosecute. The defendants were brought to trial in New Orleans before a judge of the federal Circuit Court for the District of Louisiana, William B. Woods, E. John Ellis, R.H. Marr, and W.R. Whitaker represented the defendants at the trial, which took place during the Circuit Court's 1874 April Term.

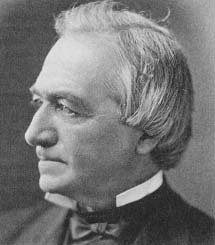

Little is known about the actual trial, as the real action was yet to come. Cruikshank and the others were found guilty. The defense lawyers promptly appealed for a stay to Joseph P. Bradley, an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. In that day and age, individual justices of the Supreme Court were charged with hearing appeals in various parts of the country before the appeals went to the full Court in Washington, D.C. The District of Louisiana had been assigned to Bradley.

Justice Bradley granted the defense's motion to stay the guilty verdicts, and Cruikshank's case was sent to the Supreme Court for a final decision. David Dudley Field, Reverdy Johnson, and Philip Phillips joined the defense team, while Attorney-General Edward Pierrepont and Solicitor-General Samuel F. Phillips personally assisted the prosecution as both sides prepared for their arguments before the Court.

At the Court's 1874 October Term, the prosecution argued that the 1870 act and the Fourteenth Amendment gave the government the power to try and convict offenders like Cruikshank. The defense argued that the Fourteenth Amendment gave the federal government authority to act only against state government violations of civil rights, but not against one citizen's violation of another's civil rights, like Cruikshank's violation of Nelson and Tillman's rights. The defense's argument, that Congress could legislate against only "state action," would have the effect of leaving the federal government powerless to prosecute lynch mobs and groups such as the KKK. African-Americans would be protected only by their state courts against white violence, which in the South, of course, meant no protection at all.

Justice Joseph Bradley granted the defense's motion to stay the guilty verdicts, paving the way for a Supreme Court decision in Cruikshank.

Justice Joseph Bradley granted the defense's motion to stay the guilty verdicts, paving the way for a Supreme Court decision in Cruikshank.

Additional topics

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationNotable Trials and Court Cases - 1833 to 1882U.S. v. Cruikshank: 1875 - Southern Racism Makes A Comeback, Supreme Court Delivers A Crushing Blow, Suggestions For Further Reading