Daniel Sickles Trial: 1859

Cold-blooded Murder Or Justifiable Homicide?

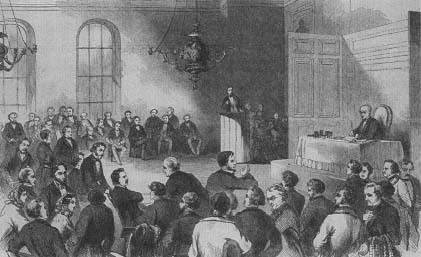

Ould opened with a sarcastic attack on Sickles' desecration of the Sabbath by a "deed of blood" against an "unarmed and defenseless victim." Noting that Sickles "bravely" and "fully prepared" himself with three guns, Ould portrayed the slaying as deliberate, premeditated, and merciless—a clear case of murder "no matter what may be the antecedent provocations in the case." Of course, it was precisely these "antecedent provocations," or Teresa Sickles' adultery, that everyone, including the jurors, were most interested in and exactly what the defense planned to spotlight in its case.

The defense's version of the slaying was distilled to its essence in John Graham's opening statement: "The injured husband and father rushes upon" the "confirmed and habitual" adulterer "in the moment of his guilt, and under the influence of a frenzy executes upon him a judgment which was as just as it was summary." Generously sprinkling his statement with Biblical quotations, Graham described Sickles' action as no less than the execution of "the will of Heaven."

Just in case the jury didn't accept Dan Sickles as one of the Lord's avenging angels, defense attorney Graham argued with equal fervor that the provocation had so unbalanced the defendant's mind that he could not be held accountable for his actions: "If he was in a state of white heat, was that too great a state of passion for a man to be in who saw before him the hardened, the unrelenting seducer of his wife?"

By the end of Graham's three-day statement, it was obvious Key would be the real defendant in the trial. Sickles' lawyers clearly planned to paint the victim as a lecher who richly deserved his fate at the hands of the accused. Despite this unveiling of the defense strategy, Ould did nothing to expose the hypocrisy of Sickles, who himself was vulnerable as a notorious philanderer. Instead, Ould contented himself with calling a series of eyewitnesses to the slaying who merely repeated the same tale in slightly different words.

The defense called numerous witnesses who attested to Sickles' mental anguish at the time of the slaying. Former Secretary of the Treasury Robert J. Walker declared Sickles was in "an agony of despair, the most terrible thing I ever saw in my life.… I feared if it continued he would become permanently insane." Sickles was so racked with sobs during Walker's testimony that he had to be ushered from the courtroom to compose himself. As he left, many in the audience wept.

When the defense attempted to introduce Teresa Sickles' confession into evidence, Ould leapt to his feet objecting that it was inadmissible as both hearsay and a privileged communication between husband and wife. Judge Crawford sustained him on the common law principle that putting such a document into the public record might do irreparable harm to the marriage. Judge Crawford's instruction to the jury to ignore the confession was so much wasted breath. The confession was reproduced in full on the front page of the April 23, 1859 issue of Harper's Weekly.

Time and again as the defense tried to introduce evidence of the adultery, prosecutor Ould furiously objected and Stanton responded with withering sarcasm. Trapped by the precedent of his own ruling in a similar case, Judge Crawford was forced in the end to permit the defense to present some evidence proving the adultery. However, the real damage was done in the uneven exchanges between Ould and Stanton, who skillfully maneuvered the prosecutor into seeming to conceal, if not excuse, infidelity and debauchery.

Assistant prosecutor Carlisle did his best to refute the defense claims of justifiable homicide and/or temporary insanity in his final statement before the jury. But, he couldn't compete with defense attorney Stanton's soaring and thunderous expression of indignation over the sanctity of the American family and the rights of the betrayed American husband. Wrapping himself and his client in the cloak of virtue, Stanton declaimed that a "higher law" than those enacted by human legislators "was written in the heart of man in the Garden of Eden" and that this law and even the laws of self-preservation set death as the penalty for seducing another man's wife. Inevitably, Stanton proclaimed, once a wife has "surrendered to the adulterer, she longs for the death of her husband, whose life is often sacrificed by the cup of the poisoner or the dagger or pistol of the assassin."

Before the case went to the jury April 26, Judge Crawford pointedly instructed the jurors that, in the eyes of earthly law, any delay between becoming aware of an adultery and the slaying of the adulterer by an enraged husband made the killing deliberate murder, or at the very least manslaughter.

Sickles' defense team successfully portrayed their client as temporarily insane. The jury returned a verdict of "not guilty" in less than one hour.

Sickles' defense team successfully portrayed their client as temporarily insane. The jury returned a verdict of "not guilty" in less than one hour.

When the jury returned in a little over an hour and, to no one's surprise, delivered a verdict of "Not Guilty," it was greeted by three cheers and sparked a spirited celebration among spectators and the defense team. The usually dour Stanton performed a jig on the spot. That evening 1,500 people joined Sickles in a victory party.

Additional topics

- Daniel Sickles Trial: 1859 - Public Opinion Turns Against Sickles

- Daniel Sickles Trial: 1859 - Mobilizing The Defense

- Other Free Encyclopedias

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationNotable Trials and Court Cases - 1833 to 1882Daniel Sickles Trial: 1859 - Lafayefte Park Killing, Mobilizing The Defense, Cold-blooded Murder Or Justifiable Homicide?, Public Opinion Turns Against Sickles