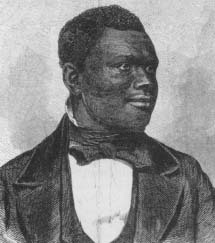

Rendition Hearing Of Anthony Burns: 1854

Dana For The Defense

No doubt Burns would have been returned quickly to Suttle and Virginia except for the intervention of the famous abolitionist lawyer Richard Henry Dana, Jr., best remembered for his book, Two Years before the Mast. Dana forced his way into the courtroom and offered to represent Burns. Burns refused, saying, "It is of no use, they have got me.… I shall fare worse if I resist." But Dana asked Loring for a delay so that Burns could have time to consider whether or not to accept his offer. He argued that Burns was in no state to decide anything at that moment. Loring asked Burns directly what his wishes were. Burns made no answer. Loring then asked him if he wanted time to consider his situation. Burns, still unsure of what answer to give, said nothing. Loring then answered for him, saying, "Anthony, I understood you to say you would?" Burns agreed and Loring adjourned the hearing for two days.

A rendition hearing was supposed to be a summary proceeding, but the case took on many of the aspects of a full-blown trial. Although Dana had delayed the hearing, he still did not officially represent Burns. Hesitant to approach him directly, Dana sent two black men, the Reverend Leonard A. Grimes and Coffin Pitts, and the white abolitionist Wendell Phillips, to talk to him. When a marshal blocked their entry, Loring ordered him to let Burns see "a few friends." Once the three were admitted they persuaded Burns to accept Dana as counsel. Meanwhile, Dana was seeking co-counsel. After approaching several established lawyers in vain, he accepted the services of Charles Mayo Ellis, a young attorney, who volunteered his help.

When Burns met with Dana, he again said that he feared severe punishment, such as being sold on the New Orleans slave market or beaten, if he resisted return. Still the attorneys pressed him, hoping, despite the odds, to convince Loring not to remand Burns to slavery. But even if Burns were returned, a long hearing would provide useful propaganda for the abolitionists by showing the Fugitive Slave Act's blatant unfairness. Regardless of the outcome for Burns, other fugitives might benefit.

Anthony Burns was declared to be the property of Charles Suttle and was returned to him.

Anthony Burns was declared to be the property of Charles Suttle and was returned to him.

Additional topics

- Rendition Hearing Of Anthony Burns: 1854 - Abolitionists Mobilize

- Rendition Hearing Of Anthony Burns: 1854 - Tracked Down In Boston

- Other Free Encyclopedias

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationNotable Trials and Court Cases - 1833 to 1882Rendition Hearing Of Anthony Burns: 1854 - Tracked Down In Boston, Dana For The Defense, Abolitionists Mobilize, Judge's Rulings Favor Master