John Francis Knapp And Joseph Jenkins Knapp Trials: 1830

Trail Leads To Knapps

Crowninshield was promptly arrested, but he kept quiet since he could not implicate Francis or Joseph Knapp without confessing to his role in the murder. Unfortunately, Crowninshield had told another one of his criminal acquaintances, John Palmer, about the Knapps' involvement. Palmer wrote a blackmail letter to the Knapps, but it was received instead by the Knapps' father. The elder Knapp turned the letter over to the police, who arrested the Knapp brothers. After Joseph Knapp confessed, Crowninshield realized that no hope was left and hung himself in his prison cell.

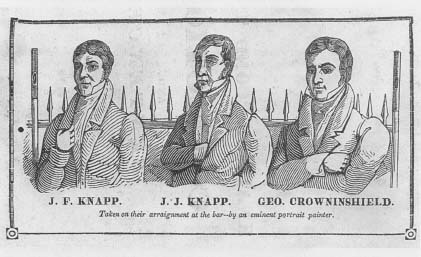

The Knapp brothers and Richard Crowninshield at their arraignment.

The Knapp brothers and Richard Crowninshield at their arraignment.

To prosecute the Knapps, the Massachusetts attorney general used the distinguished Daniel Webster. Born in 1782, Webster had practiced law in New Hampshire for a while before coming to Boston, which he would eventually leave for service in the federal government. Like many attorneys in private practice at the time, Webster occasionally worked for the state as a prosecutor.

The Knapps were charged with being accessories to murder. Both Francis and Joseph Knapp were to be tried before the Salem division of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. The judges were Marcus Morton, Samuel Putnam, and Samuel S. Wilde. For their defense, the Knapps were represented by F. Dexter and W.H. Gardiner. Francis Knapp was to be tried first, and the most important issues would be addressed in his trial.

Francis Knapp's trial was set for the court's 1830 July Term. Webster knew that his biggest difficulty lay in the fact that Richard Crowninshield, the actual murderer, had committed suicide before he could be tried and convicted. Under the ancient common law of England, which was the primary influence on the legal principles of all American states, accessories to murder could not be convicted unless (1) the actual murderer had been convicted, or (2) the accessories had been present at the time of the murder. Crowninshield was dead, and the Knapps had been 300 feet away in the street at the time of the murder.

Like every good prosecutor, Webster laid the foundation for his case by appealing to the jury's emotions. He described Captain White, who had gone to sleep on the night of the murder unaware of his nephews' plot:

A healthful old man to whom sleep was sweet, the first sound slumbers of the night held him in their strong embrace.

Webster went on to portray Crowninshield's stolen entry into White's home:

With noiseless feet he paces the lonely hall half lighted by the moon; he winds up the ascent of the stairs … beholds his victim before him … the moon resting on the grey locks of this aged victim shows him where to strike.

As to Crowninshield's suicide, Webster assured the jury that divine justice was punishing Crowninshield's soul:

A vulture is devouring it.… It can ask no sympathy from Heaven or Earth.

Dexter and Gardiner tried to keep the focus of the trial on the fact that Webster had not satisfied the legal requirements for conviction:

Upon this evidence the prisoner cannot be convicted as a principal in the murder. A principal in the second degree, according to the law of England, is by our statutes an accessory before the fact, and cannot be tried until there has been a conviction of the principal.

Additional topics

- John Francis Knapp And Joseph Jenkins Knapp Trials: 1830 - Verdict Hangs On Legal Definition

- Other Free Encyclopedias

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationNotable Trials and Court Cases - 1637 to 1832John Francis Knapp And Joseph Jenkins Knapp Trials: 1830 - Trail Leads To Knapps, Verdict Hangs On Legal Definition, Suggestions For Further Reading