John Fries Trials: 1799

Defendant: John Fries

Crime Charged: Treason

Chief Defense Lawyers: First trial: Alexander Dallas, James Ewing, and William Lewis; second trial: none

Chief Prosecutors: First trial: William Rawle and Samuel Sitgreaves; second trial: Jared Ingersoll and Rawle

Judges: First trial: James Iredell and Richard Peters; second trial: Samuel Chase and Peters

Dates of Trials: First trial: April 30-May 9, 1799; second trial: April 24-25, 1800

Place: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Verdict: Guilty, both trials

Sentence: Hanging. However, President John Adams pardoned Fries.

SIGNIFICANCE: John Fries' fate hinged on the interpretation of his actions, whether they constituted riot or levying war, i.e., treason.

In 1798, the U.S. Congress, anticipating a possible war with France, passed a tax to be laid according to assessed values on slaves, lands, and houses. The legislation, well publicized in urban areas, was little known or understood in some rural areas. This lack of understanding, particularly in northeastern Pennsylvania where many residents knew only German, led to confrontations with excise officers as they tried to examine property. One series of incidents led to a charge of treason after a band of armed men from Bucks County, led by John Fries, a former Continental Army officer, forced U.S. Marshal William Nichols to release 23 men being held on charges of insurrection. No one was hurt.

As comprehension about the tax legislation grew and affairs quieted down in Bucks and neighboring Northampton counties, rumors grew in Washington that the disturbances constituted a "plot." Members of both the Federalist and Republican "parties" fantasized reasons as to why the other group would create trouble. President John Adams dispatched troops to the area.

Upon their arrival were no disturbances to quell. Instead the military sought the ringleaders of the "insurrection." At an auction, troops grabbed John Fries and others who did not scramble away quickly enough. Of these, 15, including Fries, were charged with treason and taken to Philadelphia. The only ones tried were Fries, Anthony Stahler, and Frederic Hearny.

At Fries' first trial, prosecutor William Rawle stated that an action taken to prevent the execution of a public officer's duties was "an act of levying war," i.e., treason. Fries' fears about his rights and property were insufficient reasons to justify resistance. The defense argued that Fries' action constituted riot, which was a high misdemeanor, rather than treason. Alexander Dallas spent hours weaving points of English common law into an argument that the jury had the power to decide whether actions taken constituted treason as well as whether the defendant had committed said actions. Moreover, Fries' inability to read English had left him ignorant of the excise officers' purposes. But, in his charge to the jury, Judge James Iredell made it clear that armed resistance constituted treason.

The jury found Fries guilty. However, the judges agreed to a request for a new trial since apparently one juror had formed an opinion before the trial.

But the second trial promised to be worse than the first when Judge Samuel Chase issued a written opinion prior to the trial. It was this action which brought the trial so much attention. Chase maintained English common law had no bearing on the case and that:

Any insurrection … for the purpose of resisting or preventing by force … the execution of any statute of the United States… is levying war against the United States, within the … true meaning of the Constitution.

Although prosecutor Rawle persuaded Chase to withdraw his opinion, the defense lawyers withdrew from the case. Given the mind of the court, it would be impossible to

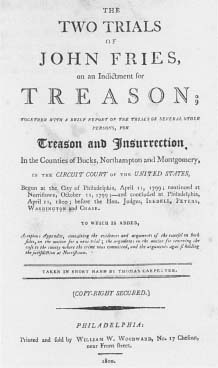

A facsimile of a published account of the trial of John Fries.

A facsimile of a published account of the trial of John Fries.

Adams sent his son Thomas to ask the defense lawyers for their briefs. He did not ask for the judges' notes—an unusual move. After consulting his cabinet members, who were opposed to much leniency, Adams first granted amnesty to all those awaiting trial, then pardoned those already convicted: Fries, Stahler, and Hearny.

— Teddi DiCanio

Suggestions for Further Reading

Davis, W.W.H. The Fries Rebellion, 1798-99. Doylestown, Pa.: 1899.

Dos Passos, John. The Men Who Made the Nation. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Co., 1957.

Elsmere, Jane Shaffer. "The Trials of John Fries." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biographv (October, 1979): Vol. CIII, No.4.

Wharton, Francis. State Trials of the United States. Philadelphia: 1849.

Additional topics

- John Peter Zenger Trial: 1735 - Zenger's Attack On The Royal Governor, Cosby Strikes Back, Hamilton's Appeal For Press Freedom

- John Francis Knapp And Joseph Jenkins Knapp Trials: 1830 - Trail Leads To Knapps, Verdict Hangs On Legal Definition, Suggestions For Further Reading

- Other Free Encyclopedias

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationNotable Trials and Court Cases - 1637 to 1832