Scottsboro Trial

History Of The Scottsboro Boys

In 1931 it was common for the unemployed to hitch rides on trains and travel from town to town in search of a job, adventure, or a way home. On March 25, nine young black men jumped on board a Southern Railroad pulling out of Chattanooga, Tennessee. Olen Montgomery, Clarence Norris, Haywood Patterson, Ozie Powell, Willie Roberson, Charles Weems,

Deputy Sheriff Charles McComb (left) and attorney Samuel Leibowitz (second from left) confer with seven of the nine youths held in the Scottsboro case, May 1, 1935. The nine black youths were charged with the rape of two white women of Scottsboro, Alabama.

Eugene Williams, Andy Wright, and Roy Wright ranged in age from twelve to twenty years. Just after the train crossed into Alabama it stopped for water in Stevenson where a fight broke out between some of the black youths and white teenagers on board. Outnumbered, the white teens either jumped or were thrown from the train as it pulled from the station.

Seeking revenge, some of the white youth reported to the Stevenson train master that the black youth had assaulted two white women still on the train. The train master telegraphed ahead to the next station, Paint Rock, Alabama, where law enforcement officers boarded the train and rounded up every black youth they could find. The two white women emerged and accused the blacks of raping them.

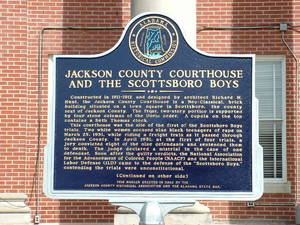

The black boys were taken to a jail in Scottsboro, Alabama, hence the name Scottsboro Boys. The arrest of the nine was the beginning of repeated trials, convictions, appeals, and more trials over the next six years.

The alleged rape victims in the Scottsboro case were Victoria Price, age twenty-one, and teenager Ruby Bates. Price and Bates were from poor families who lived in the racially mixed town of Huntsville, Alabama. They, like the Scottsboro Boys, were riding the rails in search of work. When questioned by law enforcement officers they stated they had been beaten and raped by the black boys on the train.

Less than two hours after the alleged attack, however, Scottsboro physician Dr. R. R. Bridges examined Price and Bates and found no cuts, bruises, blood, or other injuries consistent with an attack. He reported the women were calm and did not appear to be under stress.

On March 31 all nine of the Scottsboro Boys were indicted for rape. Within weeks juries convicted and sentenced eight of the young men to death in the electric chair. Twelve-year-old Roy Wright's ordeal ended in a mistrial when eleven of the jurors held out for the death penalty but one juror disagreed.

Since the arrest of the Scottsboro Boys, anger and dismay had been growing across the United States and in other parts of the world over what appeared to be racially motivated arrests and prosecution of the boys. Demonstrations in support of the Scottsboro Boys occurred outside a number of U.S. embassies in Europe. In 110 American cities, 300,000 black and white workers gathered to protest the convictions on May 1.

On May 5 in Washington, D.C., some 200,000 supporters demanded freedom for the Scottsboro Boys. The International Labor Defense (ILD), the legal arm of the American Communist Party, declared the case a racial "frame-up" and example of the oppression of black people in the United States. ILD took over the legal appeal process for the boys when the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Persons (NAACP) withdrew from the case due to the nature of the charges.

In January 1932 the Alabama Supreme Court affirmed all the convictions and death sentences with the exception of Eugene Williams. In November, however, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Powell v. Alabama that Alabama had denied the defendants proper legal representation or due process guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. The Fourteenth Amendment states that no state shall "deprive any person of life, liberty or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." Due process means fair treatment in all phases of the criminal justice system.

For the second round of trials ILD called in a well-known criminal defense attorney, Samuel Leibowitz. The medical testimony of Dr. Bridges convinced Leibowitz of the boys' innocence. He had never before been associated with racial issues but was appalled at what he viewed as the extreme unjust prosecution of the Scottsboro cases. Leibowitz worked for several years on the cases but did not charge any fees.

Haywood Patterson's second trial was before Alabama judge James Horton in March 1933. The trial took a dramatic turn when Ruby Bates stated that she and Price had made up the entire story. Price, however, stayed with her original testimony that they were raped. The jury again delivered a guilty verdict and the death penalty. Judge Horton, believing the verdict unjustified, granted a motion for a new trial. In December 1933 a jury again found Patterson guilty and sentenced him to die. About the same time, Clarence Norris endured his second trial, which ended with a conviction and the death penalty.

Leibowitz, stunned by the verdicts, appealed unsuccessfully to the Alabama Supreme Court, but moved the cases on to the U.S. Supreme Court. In April 1935 the Supreme Court reversed both convictions in Norris v. Alabama. The Court found that black Americans had been excluded from serving on the juries; therefore neither Patterson nor Norris had been judged by their equals or peers. The ruling meant the trials violated the Fourteenth Amendment's guarantee to equal protection under the law.

The following excerpt reports on Patterson's fourth trial held in January 1936. The presiding judge was William W. Callahan. Attorneys prosecuting Patterson were Melvin C.

Protestors of the Scottsboro verdict march in Washington, D.C., January 1, 1934. After the nine black youths were falsely charged and convicted of rape, many demonstrated asking for the boys' freedom.

Hutson and Thomas E. Knight Jr., the lieutenant governor of Alabama. Defending Patterson were Leibowitz and C. L. Watts. Watts was an Alabama lawyer brought into the Scottsboro case by Leibowitz.

The jury again consisted of only whites, in this case twelve white farmers. The Supreme Court decision of Norris v. Alabama was dealt with by having five blacks in the pool from which the jury was selected. All five, however, were eliminated by the prosecution.

The defense charged numerous times during the two-day trial that Judge Callahan was impatient and acted annoyed by the defense. His comments repeatedly suggested the defense attorneys were wasting everyone's time. The defense moved several times for a mistrial since this conduct influenced the jurors against the defense. Judge Callahan denied all motions for a mistrial.

Judge Callahan went so far as to halt Patterson's trial for a few hours while jurors were chosen for the trials involving Andrew Wright and Charles Weems, which were to be held the following week. As described under the subtitle "Defense Objections Overruled" Wright and Weems sat "manacled" (shackled) in chains in full view of the Patterson jurors during this time. The sight of the black youth in chains, defense attorneys argued, would prejudice the jurors against them.

The defense was able to enter the previous testimony of Dr. R. R. Bridges, about his examination of Price and Bates hours after the alleged attack and how there was no evidence of such an attack. Patterson plus four other Scottsboro Boys were put on the stand and testified that they had not touched Price or Bates; the boys further testified they had never even seen the women. Discounting Dr. Bridges and the boys' words, prosecutor Hutson, in closing statements, emotionally pleaded with the jury to protect the "rights of womanhood of Alabama" and convict Patterson.

Additional topics

- Scottsboro Trial - Things To Remember While Reading Excerpts From "scottsboro Case Goes To The Jury":

- Other Free Encyclopedias

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationCrime and Criminal LawScottsboro Trial - History Of The Scottsboro Boys, Things To Remember While Reading Excerpts From "scottsboro Case Goes To The Jury":