Stamp Act

The Stamp Act was the English act of 1765 requiring that revenue stamps be affixed to all official documents in the American colonies. In 1765 the British Parliament, under the leadership of Prime Minister George Grenville, passed the Stamp Act, the first direct tax on the American colonies. The revenue measure was intended to help pay the debt incurred by the British in fighting the French and Indian War (1754–63) and to pay for the continuing defense of the colonies. Unexpectedly and to Parliament's great surprise, the Stamp Act ignited colonial opposition and outrage, leading to the first concerted effort by the colonists to resist Parliament and British authority. Though the act was repealed the following year, the events surrounding the tax protest became the first steps towards revolution and independence from England.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the economies of the American colonies had matured. The colonies chafed under the rules of British mercantilism, which sought to exploit the colonies as a source of raw materials and a market for the mother country. During the French and Indian War, the colonies asserted their economic independence by trading with the enemy, flagrantly defying customs laws, and evading trade regulations. These actions convinced the British government to bring the colonies into proper subordination and to use them as a source of revenue.

Colonists protest the Stamp Act of 1765 by burning Stamp Act papers in Boston.

The colonists had become accustomed to a limited degree of British regulation of trade. The Navigation Acts of 1660, for example, stipulated that no goods or commodities could be imported into or exported out of any British colony except in British ships. Later legislation stipulated that rice, molasses, beaver skins, furs, and naval stores could be shipped only to England. Duties were also imposed on the shipment of certain articles, such as rum and spirits. However, the Stamp Act was the first direct tax, a tax on domestically produced and consumed items, that Parliament ever levied upon the colonists.

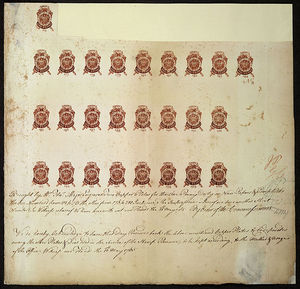

The Stamp Act was designed to raise almost one-third of the revenue to support the military establishment permanently stationed in the colonies at the end of the French and Indian War. The act placed a tax on newspapers, almanacs, pamphlets and broadsides, legal documents of all kinds, insurance policies, ship's papers, licenses, and even playing cards and dice. These documents and objects had to carry a tax stamp. The act was to be enforced by stamp agents, with penalties for violating the act to be imposed by vice-admiralty courts, which sat without juries.

Parliament passed the act without debate. Similar stamp acts had become an accepted part of raising revenues in England, leading parliamentary leaders to mistakenly believe that the measure would generate some grumbling but not defiance. The colonies thought otherwise, interpreting the Stamp Act as a deliberate attempt to undercut their commercial strength and independence. They were also concerned about the implicit assault on their rights to trial by jury, the unprecedented use of a direct tax as a means of raising imperial revenue, and the allinclusive character of the law that applied to all thirteen colonies.

The colonists raised the issue of taxation without representation. Some colonists drew a distinction between the English regulation of trade, which was viewed as legal, and the English imposition of internal taxes on the colonies, which was perceived to be illegal. Theories and arguments against the Stamp Act were distributed from assembly to assembly in the form of "circulars." PATRICK HENRY introduced seven resolutions against the Stamp Act in the Virginia House of Burgesses, five of which were passed. All seven resolutions were reprinted in newspapers such as the Virginia Resolves. These and other pamphlets pressed Parliament to repeal the act.

In October 1765 nine of the thirteen colonies sent delegates to New York to attend the Stamp Act Congress. The congress issued a "Declaration of Rights and Grievances," declaring that English subjects in the colonies had the same "rights and liberties" as the king's subjects in England. The congress, noting that the colonies were not represented in Parliament, concluded that no taxes could be constitutionally imposed on them except by their own legislatures. Petitions embracing these resolutions were prepared for submission to the king, the House of Commons, and the House of Lords.

The Stamp Act also led to the formation of formal opposition groups in the colonies. The Sons of Liberty, which remained active until the American Revolution, grew directly out of the Stamp Act controversy. Often organized by men of wealth and standing in the community, Sons of Liberty groups were active in towns throughout the colonies, and their members often engaged in violent acts. In Boston, for example, an angry mob forced the stamp agent to resign.

Colonial merchants also organized an effective economic boycott, with merchants in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia entering into nonimportation agreements. The drop in trade was dramatic, leading to the BANKRUPTCY of some London merchants. In addition, businesses flouted the act by carrying on their trade without purchasing the required stamps.

The virulence of the opposition to the Stamp Act surprised the colonists as much as the British government. The costs of simply maintaining order in the colonies threatened to negate any economic advantages of the legislation. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, as the colonial agent for Pennsylvania, testified before the House of Commons in early 1766 that any attempt to enforce the Stamp Act by the use of troops might bring on rebellion. His call for repeal was joined by a committee of English merchants, which cited the dire economic consequences the act was producing. When Grenville's government fell from power, the new prime minister, Marquis of Rockingham, moved quickly to resolve the issue. In February 1766 the repeal of the Stamp Act was approved by the House of Commons. The House of Lords, under pressure from the king, approved the repeal as well, which became effective in May 1766. Nevertheless, in the Declaratory Act of March 1766, Parliament ominously asserted that it had full authority to make laws that were legally binding on the colonies.

England's need for revenue and Parliament's conviction that it alone, in the empire, was sovereign did not end with the repeal of the Stamp Act. New and harsher laws were enacted in succeeding years, producing a predictable reaction from the colonies. The full significance of the Stamp Act crisis is that it served as the initial event unifying all the colonies in their resistance to parliamentary authority. The opponents to the act laid a theoretical foundation for later revolutionary thought in their elaboration of the doctrine of consent by the governed. The act led to the creation of enduring resistance groups, such as the Sons of Liberty, which were capable of springing into action at the least provocation. And it established precedents for later resistance, including the use of a congress, the issuance of circulars, the resort to legislative resolves, and the adoption of economic sanctions. Most importantly, the Stamp Act crisis made the colonists more aware of the identity of their interests, which would ultimately lead them to think of themselves as "Americans."

FURTHER READINGS

Morgan, Edmund S. and Helen M. 1995. The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press.

Thomas, Peter David Garner. 1975. British Politics and the Stamp Act Crisis: The First Phase of the American Revolution 1763–1767. New York: Clarendon Press.

CROSS-REFERENCES

Continental Congress; Declaration of Independence; Paine, Thomas; "Stamp Act" (Appendix, Primary Document); Townshend Acts; War of Independence.

Additional topics

Law Library - American Law and Legal InformationFree Legal Encyclopedia: Special power to Strategic Lawsuits against Public Participation